Pierangelo Masciadri has been selling ties from his small atelier on the shores of Lake Como since the 1970s, but the pandemic has forced him to take his sales online.

As businesses across Europe closed their doors during last year’s lockdowns Masciadri, who has tens of thousands of customers around the world, including former US president Bill Clinton, set up shop on eBay. “It was quite a big revolution for my business,” Masciadri said.

“Who would have thought to learn what search engine optimisation was at the ripe old age of 70 . . . When the first order arrived, I couldn’t believe it was really happening.”

He is not alone. Italy’s booming goods exports have become a key driver of the country’s economic recovery from last year’s historic recession, fuelled by a rapid increase in businesses using digital technology.

By April, goods exports were 6 per cent above January 2020 levels — the strongest growth rate of any major eurozone economy, compared with rates of less than 1 per cent in France and Germany. As a result, Italy’s goods trade surplus has surged since the start of the pandemic.

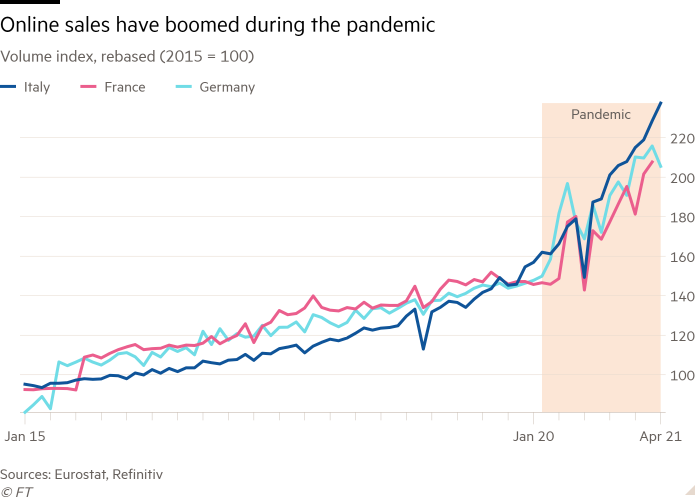

Online retail sales volumes were more than 50 per cent up in January 2020, well ahead of the eurozone’s 42 per cent average.

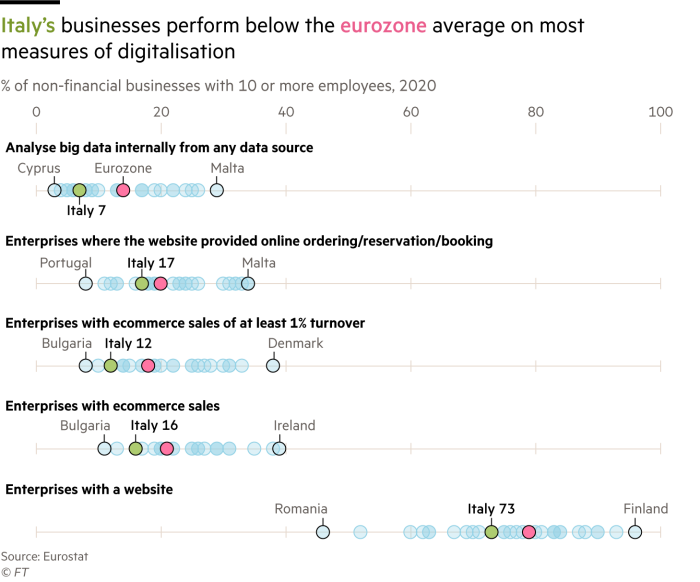

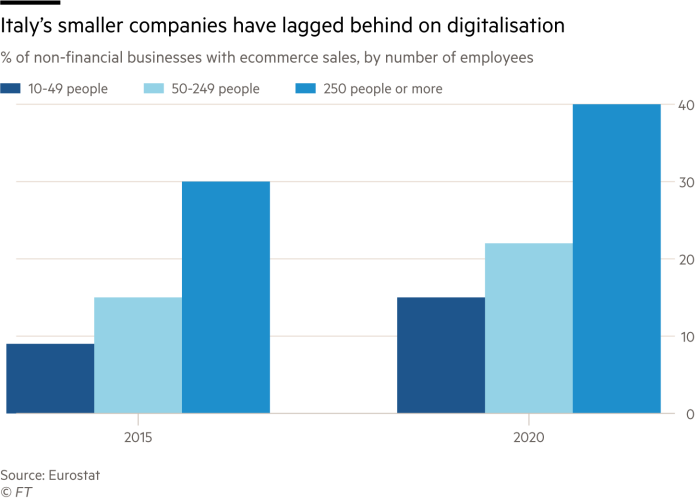

It is not before time. Italy has long been a digital laggard. In 2015, a year before Rome launched an industrial plan that aimed to boost technology investment, fewer than one in 10 small- and medium-sized businesses sold online — just half the eurozone average.

This has since improved by 6 percentage points, but it still leaves the vast majority without an online sales operation. This has hampered Italy’s productivity, which has not only been battered by the crisis but has barely grown in real terms since the beginning of the millennium.

Andrea Basso, sales director of Aptos Italy, a company that sells retail technology mainly to small- and medium-sized businesses, said that because many companies had faced “extremely limiting situations” during the pandemic “they have therefore been forced to find creative solutions, accentuating the digitalisation process”.

“Very small companies, in particular, have realised the importance of an extremely quick reaction time if they want to compete,” Basso added.

Dario Carosi, who runs Mondo Convenienza, which designs, sells and distributes furniture and home accessories, said digital investment had been the key to keeping the company’s turnover at 70 per cent of normal levels, even during the most acute phase of the pandemic.

The digital division the company set up in 2017 “saved us”, Carosi said. The company has since shifted more resources into digital projects in recognition that their customers’ move online is here to stay.

Digitalisation and innovation are also at the core of Italy’s ambitious programme of post-pandemic reforms. Mario Draghi, Italy’s prime minister, took office earlier this year pledging to overhaul the country’s notoriously slow bureaucracy and legal systems.

He wants to use the €205bn that Rome will receive as its share of the EU’s recovery fund to digitise the economy, as well as on infrastructure projects, climate and environmental initiatives, education and health.

Speaking at a press conference last month, Draghi said digitalisation was “of utmost importance” to narrow socio-economic inequality and help the economy recover from Covid-19.

“It is one of the most urgent priorities of the government,” Draghi said. “Many of the projects [in other sectors of the economy] could not be carried out without taking a step forward by digitising our public administration and our planning ability.”

Massimo Rodà, a senior economist at industry lobby group Confindustria, said digitalisation was “a decisive factor in the economic development of a country and in improving its competitiveness”.

“It changes consumption and production patterns, business models, preferences and relative prices and also affects policy-relevant variables such as employment, productivity and inflation,” he added.

This is helping to ease the economic impact of the pandemic. Italy was the only major eurozone economy to grow in the first quarter of this year. Its output expanded by 0.1 per cent from the previous three months; by contrast, the eurozone as a whole logged a contraction of 0.3 per cent.

“Italy’s entire future lies in digitalisation and the current circumstances have led to the unblocking of a modernisation process for a country that has been moving at a sluggish pace for too long,” said Irene Finocchi, a professor of computer science at LUISS University in Rome. “This is finally an opportunity to catch up with other countries.”

This shift during the pandemic means more Italian companies are enjoying the benefits of their unexpectedly speedy transition to digital commerce.

Maura Maitini runs a shop selling religious articles and liturgical vestments in the medieval town of Assisi, a popular destination for pilgrims. She said her business had been “almost flattened by the pandemic” — until she set up shop online.

“The first item we sent out was a chalice for the Holy Mass,” she said. “Of course, human contact is important, but faith is also evolving with technology. Sometimes, when someone orders a pendant or a rosary online, I bless it in church before sending it off.”

Source: Financial Times